|

This page is a reproduction

of part of the "Telling Tales" website by Ernie Weiss concerning

the school.

Ernie died in August 2006 and his site closed sometime later, but I have

since salvaged it from an internet archive

It is now complete with all missing photographs reinstated, and is presented

here in virtually identical format to the original.

E-mail links are now redirected to me, and external links have been removed.

I have also included the excellent contributions by Priscilla Wilder,

née Eaves, Gay Marks, Natalie Muzlish, née Besser, plus

photographs by Lizabeth Flint

- Norman

|

St. Mary's

Town & Country School

created by Ernie Weiss, one

of the Pauls' school's first pupils

Abstract

Despite its name - the "Town

& Country" portion was a post-war addition - St. Mary's School was an

independent (private) non-denominational co-educational school. To many of us

former pupils, however, it was much more than this - it was a remarkable and

unique learning experience.

Being too young during my time there to

be aware of the differing approaches to and theories of education, I guess that

St. Mary's must have been a "progressive" school, with its Froebel

leanings and its group learning practices. To what extent the school was

"progressive" is debatable - as, for instance, we still addressed our

teachers formally (viz: Mrs Eaves. Miss Gardener, Mrs Paul). The school seemed

heavily biased to the learning of languages and the arts from an early age,

sacrificing time devoted to the sciences and technology. (Some brief notes

about "Progressive Education" may be seen on The Beltane School web

page (my second school) via my home page under Links below.)

The school was owned and run by

Elizabeth Paul, assisted for most of this time by her husband Heinz Paul. They

were of German Jewish origin. They bought the school as a going concern in 1937

when it was still at 1, Belsize Avenue, Hampstead (where I believe the original

school started a few years earlier - in what form I know not). The Pauls

relocated and restarted the school in a pair of adjoining

"semi-detached" houses at 16 Wedderburn Road (between Fitzjohn's

Avenue and Belsize Park) close by in Hampstead, London N.W.3. during the summer

of 1937, initially as a day school. In September 1939 it became a boarding

school on evacuating London due to the outbreak of World War II.

Shortly after the war ended in 1945,

the school split. The main part returned to within half a mile of its pre-war

location - to 38-40 Eton Avenue (into another pair of leased semi-detached

houses) just off Swiss Cottage - where it remained until its demise in 1982.

The "country" boarding section moved to Stanford Park in

Leicestershire - but this only lasted for a few years.

Preamble

1. The Early Years & Boarding School During

WWII

a. A Memoir by Ernie

Weiss

b. Reminiscences by

Priscilla Wilder, née Eaves

2. The Middle Years -

Eton Avenue

Memories

a. 1947-48 by Gay Marks

b. 1953-61 by Natalie

Muzlish, née Besser

Photo Montage - from the

early 1960's

Preamble

The following notes are former pupil

personal memories. Essentially historical, these do not purport to be an

authoritative history of the school, however. Part 1 of today's web site

records something of the first eight years both of the school's existence and

of my formal education - mainly my war-time school experiences. This was

originally published as one web page within my "Telling-Tales" web

site. Then, in the autumn of 2003, another former pupil contributed with her

own (and more mature) memories of this era of the school's existence.

Before the above contribution, however,

on reading my web page via the Friends Reunited web site, a more recent (Eton

Avenue) pupil was stimulated to ask if she could add some of her own memories.

These were written and uploaded in 2002 and are shown in Part 2. Since then, a

few more former pupils have emerged, expressing some interest to make further

contributions - for example, a brief contribution of the late 1940s and the

Photo Montage (also in Part 2). These combinations progressively add interest.

In spite of another web site about life at the school in the 1960's (Norman

Barrington's - see Links below) there are still gaps: chiefly the immediate

post-war eight years and the school's last 15 years.

Some questions arise. Does a more

definitive school history exist? Is there anyone out there who has any more

memories of the school pre-World War II? Has anyone a pre-1960 copy of the

school prospectus? Are there any memories from Stanford Park? Where and for how

long did the "Country" part of St. Mary's exist between Stanford Park

(which was a school) and Hedgerley Wood (which was the Pauls' weekend home and

not a school)?

Most of us have very fond and positive

memories of the school in general and Mrs Paul and some of her staff in particular.

Hence, we keenly invite anyone who would like to record their own experiences

at the school to contribute. Contact may be made by email direct. Consolidation of such memories

and information would help to enrich and create a more comprehensive record

of this unique educational enterprise.

* * *

1. The Early Years

& Boarding School During WWII

Formal education started

for me at St. Mary's School in 1937, about a couple of months before my fifth

birthday. As Mrs Pauls purchase and rebirth of the school was that year, I must

have been among its first pupils. I remained there for my entire primary

education, or what Mrs Paul later termed the "Junior School." At the

end of the second world war in 1945 I transferred to The Beltane School.

On my first morning, I recall being

told on arrival to play in the sand pit, which was located in a large ground

floor bay window. Unfortunately, the school cat(s) had been there before me!

Nothing else of note comes to mind from my first couple of happy years at

school, except that I was much more enthusiastic about graphic art and finding

out how things and nature work, than about the three "R’s".

Another memory was my appendicectomy,

at The London Clinic, when I was almost six. A huge get well card arrived at my

bedside from all 15-18 of my school class mates. Five days after surgery I was

allowed up from my hospital bed for the first time. This was to see, from my

hospital room window, the 1938 Guy Fawkes fire works across London - the last

before the war put an end to these more festive rocket missiles and explosions.

We had a rather late summer holiday in

1939, in Llanmadoc on the Gower peninsula in South Wales. This was a farmhouse

holiday, with the five of us, plus my baby brother Peter's nanny - Evelyn,

alias "nurseydear" - and our closest friends, the Flemings

(originally Fleischmann): Oscar, Nina and their then teenage son Cecil. I

remember that there seemed to be endless expanses of sand and dunes, which were

about ten minutes walk through bracken and sheep cropped grass from the working

farm. It was there, on the third of September, that we heard that because of

Hitler's invasion of Poland, Britain declared war on Germany.

My father had to hurry back to London.

St. Mary's School was about to evacuate to the south west coast - so it was

arranged that Oscar would drive my sister Marian and me direct from Wales to

the school's new Devonshire location. I recall that we had to bed and breakfast

en route and the first time that I had a cooked English breakfast: egg and

bacon. Oscar was far more Jewish than we were, yet he enjoyed his bacon too!

Marian, aged five and I, not yet seven, were suddenly about to become boarders.

Along with about twenty other children of various ages, we were expected to be

relatively safe in rural England.

Marian and I had no idea then, of

course, how heart-wrenched and devastated mother must have felt, not knowing

when she would ever see us again. She returned to our London home to care for

her ageing and ailing parents, toddler Peter and with Robin already well on the

way.

Perhaps it should be explained that

only a small minority of children evacuated with their schools when the war

broke out, as these were independent schools and applied chiefly to those whose

parents could afford the fees. Mass evacuation started with the start of the

bombing blitz several months after the start of the war. Many children

evacuated London and the larger industrial city areas to escape the worst of

the blitz. (A second wave of evacuation took place in 1944, when the V1

"doodlebugs" attacked Kent and the Greater London area.)

Most of these children evacuated

without their parents to temporary "foster" parents in rural and the

less industrialized provincial areas. Many were sent to the north of England,

joining the local schools. Some suffered very difficult and miserable times,

with mutually alien cultures, dialects and customs. Northerners were often

deeply suspicious of Londoners, believing them to be delinquents and in the

myth of the "corrupt and evil city" and the likelihood of its

population being so contaminated!

St. Mary's School left London to escape

from the imminently expected blitzkrieg. So, it changed from being a day school

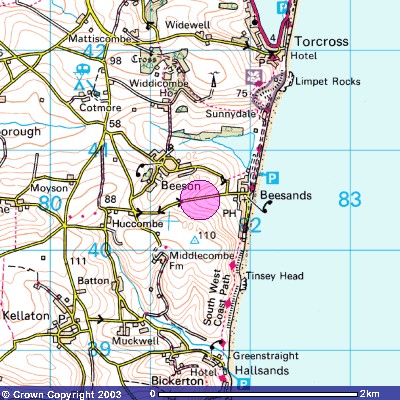

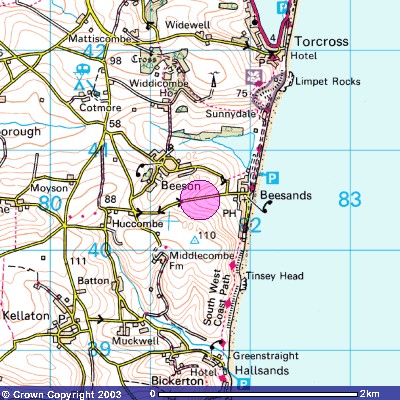

to a boarding school.  Beesands is a tiny village on the Start Bay

shore between Torcross and Start Point in the southern most part of Devonshire

known as the South Hams. This beautiful fertile region of English countryside

lies between the English Channel and perhaps the most rugged barren "last

wilderness" in the southern half of Britain: Dartmoor.

Beesands is a tiny village on the Start Bay

shore between Torcross and Start Point in the southern most part of Devonshire

known as the South Hams. This beautiful fertile region of English countryside

lies between the English Channel and perhaps the most rugged barren "last

wilderness" in the southern half of Britain: Dartmoor.

The school house was a fairly large

farmhouse, situated about a quarter of a mile along the shore just north of

Beesands, towards Torcross - shown on the map as the small square at the

north-east tip of the lee (lake). It accommodated a total of about two dozen

staff and pupils. The garden, down to the beach, was enclosed by a very high

thick hedge - a very effective wind break.

We had one of England's finest beaches

literally on our doorstep - a vast expanse extending to about six miles north

of Torcross, Slapton Sands and about three miles south to Hallsands. But these

are misnomers, as the beaches are almost entirely shingle. Tragically, the sea

had just about totally eroded away the village of Hallsands and I believe that

only one or two cottages were still inhabited when we left there in

1940.

There were no caravans on the

foreshore then and for the first few months we had the beaches entirely to

ourselves. Bathing was treacherous, with steeply shelved shorelines and severe

undertow, other than at low tide and even then, never without a teacher being

present was the strict rule, I recall.

We had a wonderful time. During that

first "Indian summer" we, the younger groups, often ran around naked

within the enclosed garden. Even during the first winter, we played mostly on

the beach and foreshore. I recall little of class sessions. I think that we

were split three ways: a few under six years of age, about six of us between

six and eight, about the same number between eight to 11 and a very few older

children. I remember only three staff during that first year: the heads, Mr and

Mrs Paul and Mrs Eaves (accompanied by her two children, Priscilla and her

younger brother John, who was two or three years my senior).

Elizabeth Paul was a large, vibrant

woman, who was enterprising, imposing and assertive. Beneath her

larger-than-life macho image, I felt that there was some warmth and empathy,

which she kept hidden most of the time. She was a linguist, being fluent in

English, French and German. Heinz Paul (we nicknamed him "Higgy" -

quite why escapes me) supported his wife, mainly behind the scenes and quite

possibly was a tour de force there. I do not recall him actually teaching,

possibly not being qualified. He appointed himself largely as the general

factotum. Mrs Eaves was a gem of a primary teacher, with infinite patience,

warmth and kindness.

Strangely enough I was not homesick,

although Marian (still only five) was at times. Marian and I remained at the

school over that first Christmas holiday, our parents deciding to visit us for

the festive weekend instead, with a few very basic presents and extra clothes.

The main reason for this, I believe, was that our London home was still filled

with Jewish refugees (from father's escape line) awaiting clearance and passage

to the States. Our parents had to come by train to Kingsbridge (this branch

line later became a casualty of the "Beeching cuts") and then by

taxi, as cars and petrol were allowed only to "essential" (and

privileged) users during the war.

The funny little silly things one

remembers: mother giving Marian a bottle of scent, which she dropped and

smashed accidentally the day after they left and how much more the loss of this

memento upset me than her! One of their parting gifts to me was a tobacco tin

filled with mother's cigarette smoke, which I opened after tea that evening to

surprise the other kids with "magic." Also, I recall startling mother

with my total rejection when she suddenly switched to speaking German to us

(which I explain later).

I remember the arrival of Paul and his

cousin Natasha, Jewish refugees from Vienna, who actually witnessed the Nazis

marching into the Austrian capital - a situation which I found astonishing, in

that they still managed to escape. Paul and I became firm friends for much of

our childhood. (Paul went on, via Aldenham School and the Architectural

Association, to earn quite a reputation as an architect. It is a small world -

many years later, Marian met him and his own young family at the Caversham

Centre in Kentish Town, London - the pioneering group practice/health centre,

when it was still in Caversham Road - where Marian was the practice nurse!)

We had some beautiful walks: the Devon

South Coast footpath to Start Point lighthouse, about seven miles round trip

from the school. To Torcross too, via the mini fresh water newt pond in a glade

(with many dragon-flies, newts and water-boat-men) and climbing Jacob's Ladder

up a small rock-face to the top of the little headland to descend to the

village. Behind Torcross lay the large fresh water lagoon of Slapton Ley

alongside and just behind the beach, created by the natural silting-up process.

(I found this path again over 40 years later and the vertical iron ladder, very

overgrown but still there, exactly in proportion as I had remembered this at

the age of seven.)

Naturally, we also explored the deeply

hedged Devon lanes inland, into the farming areas, with the rich red clay soil

and hedgerows dividing cattle from crops. Red squirrels were then still quite

common, before being ousted by the grey.

The farm adjoining the school was

mainly a pig farm. We were all upset with the slaughter sessions, as we could

hear the pigs squealing for their lives. In those days they cut their throats

and let them bleed to death, harvesting the blood. A nature walk for the entire

school was organized on these afternoons, to allay our distress.

Most mornings, we had a before

breakfast run: the older kids ran about 500 yards to the village store, called

The Crab Pot (I believe it still is) and back, the younger ones ran about half

way. Breakfast was certainly welcome after that. Despite food rationing, we

always seemed to have had plenty.

Half a day each week was dedicated to

maintaining the "sea wall" just below the high tide line as best we

could, due to the immense tides and erosion taking place. This meant piling up

stones and filling gaps with as many flat stones we could find, but setting

them in a vertical plane with edge to seaward, to combat the lateral power of

the waves along the beach. Frequently, we saw massive schools of porpoises or

dolphins playing and "show-jumping" in the inshore waves.

By the time of our first holiday at

home in 1940, I had deliberately forgotten all my German, despite the boast

that the school specialized in being multi-lingual! There were three reasons

for this. Firstly, anything German I was determined to scorn and reject, as

Germany had rejected us and then became the dreaded enemy. Secondly, to insist

on maintaining two languages may have exacerbated my speech impediment - a

severe stammer. Lastly, in contrast to most refugee kids, my living-in (at

home) grandparents knew sufficient English to not have to converse with them in

German. So Marian and I lost our German, though for quite a while we could

understand when we were not meant to!

One morning we discovered that a U-boat

(German submarine) was trapped in Start Bay by a sandbank at low tide. We were

rushed inland and out of sight, lest they opened fire on us. Apparently, they

surrendered and a coast guard boat went out to officially take them prisoner

and a trawler towed them in, probably to Plymouth.

On another occasion, we were all

ushered to the back of the house when one of us noticed what looked like a mine

floating in the waves. Very bravely, Mr Paul crawled Indian fashion down to the

waters edge to investigate, eventually to return somewhat sheepishly (and wet)

with a large medicine ball bladder (like a double sized football)!

Our world was beginning to feel a

little less safe than that desired. Then, in late June 1940, about a month

after the Nazi occupation of Belgium and Holland, France capitulated to the

Germans. This meant that the Hun were amassing just across the water, with the

invasion of England due next. Thus, the school had to evacuate again, from a

potential combat area to a safer more central inland location.

As a postscript here, our move was

indeed timely and fortuitous, as a stray torpedo (I know not whose) blew-up

much of the school house a short time after we vacated it.

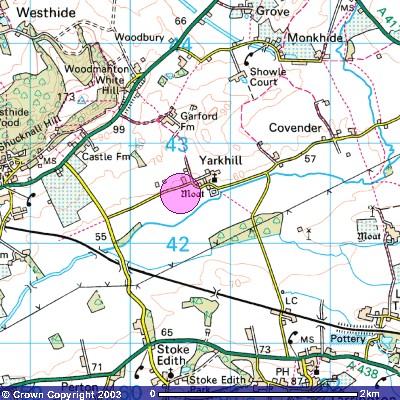

Our new location was just as beautiful

as the one we had left but in quite different ways. The only similarities were

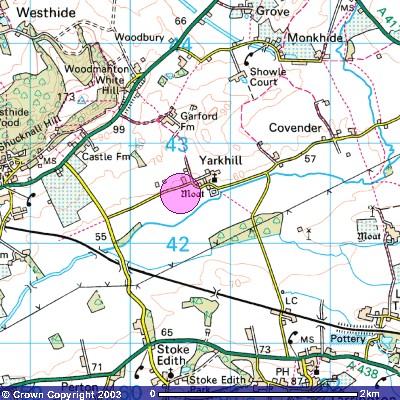

the very fertile land and its rich red soil.  Yarkhill in Herefordshire is

in the heart of rural Britain, in the rain shadow of the Welsh Black Mountains

betwixt the city of Hereford and the Malvern Hills. We moved into Yarkhill Court,

a small manor house attached to a working mixed farm, about six miles east of

Hereford and lying between the villages of Tarrington and Stretton Grandison.

Our local Great Western Railway station was Stoke Edith (now no longer existing,

I believe) less than half a mile from Tarrington and about 1.5 miles from the

school.

Yarkhill in Herefordshire is

in the heart of rural Britain, in the rain shadow of the Welsh Black Mountains

betwixt the city of Hereford and the Malvern Hills. We moved into Yarkhill Court,

a small manor house attached to a working mixed farm, about six miles east of

Hereford and lying between the villages of Tarrington and Stretton Grandison.

Our local Great Western Railway station was Stoke Edith (now no longer existing,

I believe) less than half a mile from Tarrington and about 1.5 miles from the

school.

The house was early Victorian, built

along Georgian lines: square, rural, two stories, plus attic and, unlike the

rather ornate Victorian interior decor, unpretentious. It had a large mature

yew tree by the front gate. Adjacent, stood a small church within its

graveyard, to serve the immediate district. There was no vicarage, as the

parish included one or two other churches. To one side there was a huge walled

kitchen garden, mainly overrun with course grass and horse-radish. The only

other garden was to the front, chiefly lawn ( at one time a tennis court I

believe) with the access drive from the main farm yard on the other side and to

the rear. There was also a conservatory, which we used as one classroom.

The small river Frome flowed close by,

where we often swam in the red muddy waters, which we shared with Hereford

cattle, chub, perch, water-rats and otters. This was a tributary of the river

Wye. The farm then included some of the largest hop yards outside Kent, having

its own oast-houses. Traditionally, hops were used in the breweries - but the

war created another demand: as a khaki dye. The unique aroma of hops is still

one of my favourite. Opposite the school and across the access lane was a

little moat, surrounding an islet.

Shortly after the move to

Herefordshire, I was told that father had been sent to camp. I remember my

response that he would like that, as he was good at camping (it was much later

that I learned what internment really meant). Because of this, with the

resultant shortage of funds, my sister Marian had to return home and to a local

state primary school in Highgate Village, to save on costs. But for my speech

difficulties, I probably would have joined her. It was felt, however, that such

a move may have been too brutal for me, so mother scrimped and, helped with

some patience by the Pauls, I remained at St Mary's. Naturally, the funding

problem was remedied shortly after father's release from this arbitary

imprisonment a few months later, when he could start earning a living again.

It was a sad day when Marian left. Of

necessity, having had to leave home so very young and because we were only 15

months apart in age, we had become very close. Marian's propensity to care and

nurse came to the fore very early. This probably helped her as much as her

intent to comfort me, particularly living my speech and resultant temper

frustrations with me, which she recalls more vividly than I. One legacy Marian

took away with her was her sustained wont to vegetarianism, although never as

strict or peculiar as Mrs Paul's own diet.

On seeing Marian's "new"

school I was horrified. St Michael's Primary School had separate entrances for

boys and girls, where they had to wait in lines outside, regardless of the

weather, until the bell went. Class sizes were often over 40, learning was

largely by rote and discipline was imposed with the threat of corporal

punishment. The cane was much flaunted and frequently exercised! This

antiquated and destructive system was not untypical of British state education

in the middle of the twentieth century - a regime designed to humiliate and

subdue.

St. Mary's grew in numbers within the

first year of our Herefordshire tenancy. Miss Gardener joined us, an excellent

and most enterprising young teacher, who came with and lived in a genuine

lantern roofed original Gypsy caravan, set near the top corner of the kitchen

garden. I can still see the beautifully bright hand painted decor inside and

out, and the ornate cut and bevelled glass and interior furnishings, all being

examples of the most exquisite dedicated craftsmanship.

Later, as the school numbers grew still

more, we were allocated three conscientious objectors as teachers - but I doubt

how well qualified they were, as two of the three had not much of a clue.

Children are very quick and astute in sensing weaknesses and fallacies and we

were merciless with these two. They did not survive their first term. The other

"CO" (whose name I have forgotten) turned out to be an inspired

teacher: firm, no nonsense but fair and he became very popular.

Having a myriad of mainly happy

memories of these war years, I summarize but a few of these below. We saw

little of the war, only very rarely seeing anything of the military in our

rural environment. We experienced a little of the blitz only at home during

school holidays - but met crowds of military personnel when we travelled on the

then steam trains at the end and start of school terms.

Travel then was something of a lottery:

trains were always overcrowded, we very rarely found seats, standing, or

sitting on our battered suitcases, in the corridors much of the time. Trains

were inevitably late, or cancelled - sometimes very late and then much to the

consternation of those awaiting our arrival. The railways were the butt of both

radio comedy and music-hall jokes. Many people might claim that nothing much

has changed, despite the demise of steam and, more recently, the advent of

privatization.

I recall the awful news of the

expeditionary force's fiasco at Dunkirk and the small ship flotilla coming to

the rescue - probably the greatest escape in human history. I guess that every

primary schoolchild in 1940 was expected to draw or paint a picture of this

desperate escape scene.

Mr Paul joined the Home Guard. He

looked quite like Field Marshal Montgomery when he wore his uniform and beret

and was very proud of this resemblance. He also became the local Air Raid

Warden, but there were no air raids on our district! We all knew that Mrs Paul

was the prime mover in their partnership and she really ran the school, so we

felt that she was quite happy to see him with some important community service

to undertake.

Mr Paul was also a bit of a

"ham" psychologist and took copious notes about any of our

behavioural idiosyncrasies, my stutter and tempers included. The Paul's were

foster parents, or guardians, to a young adult, Michael, of below average

intelligence. He was a big strong fellow, yet very friendly. His one passion in

life was the cinema organ, which he pretended to play most of the time. He was

forbidden to use the pianos, as he was too heavy handed but he hummed and

hammered away anywhere he could, usually at the odd window sill, with great

zeal and energy - but no finesse.

As we grew older, our classes became

more formal than those in Beesands. There was emphasis on languages and the

arts - but very little on the hard sciences. Learning was usually in mixed age

and ability sessions and we were split into small groups working on our own

subjects, problems and projects. We had weekly round table spelling games and I

shall never forget how to spell "unnecessary", as this went round the

table of about 14 of us at least four times before the right answer was given.

Father had arranged for me to have

private Hebrew study lessons. He must have had a conscience about not bringing

us up with any Jewish knowledge (we were not practising Jews) as I cannot

otherwise explain his motives. The Hebrew teacher came by train, so to save him

time, we met on Sundays at Stoke Edith station waiting room and conducted our

lessons there. These only lasted for two terms; the teacher was not the most

inspiring and so my interest was never adequately aroused to foster sufficient

motivation.

Another even briefer flirtation I had

was with the piano. Living quite close to the school, in Bartestree, was a

superb pianist, musician and teacher: Michael Mullinar. He would have been a

top concert pianist but I believe that he had some phobia about playing in

public. He gave W.E.A (Workers Education Association) lectures, however and

performed at these. They were given at the school, as Mr Paul's most prized

possession was a Bechstein concert grand piano. There were usually seats to

spare and a few of us kids were allowed to sit-in. In this way, I learned to

love classical music.

Unfortunately, despite wishing to

become an instant Schnabel, I had insufficient patience to persevere with

scales, so my aspirations in this direction were very short lived, which I have

much regretted since. Marian, however, had a few piano lessons before she left

and Mr Mulliner felt that she showed some promise. This encouraged her to

continue with lessons with another teacher in London until she started nurse

training. One summer a group of us picked Loganberries for the Mullinars in

their garden.

The ever resourceful Miss Gardener had

the idea to re-cultivate the kitchen garden. All volunteers were given plots

within the box hedged areas and competitions were set-up with prizes for the

best cultivated garden and various best produce grown, monthly every summer and

autumn terms. There were soft fruit bushes still in abundance and all they

needed was weed clearance to bear more: red and black currents, various

gooseberries, strawberries and raspberries. Also, there were other fruit trees

bearing plums, pears, apples and peaches.

There was a communal effort to clear

the horse radish. This required double digging (two spits deep) to clear the

long roots - very long hard work indeed. We used this area for high volume

crops; firstly for potatoes to help regenerate the soil, then spinach, onions

and brussel sprouts. We also kept goats, rabbits, ferrets and a few chickens

and bantams. We took it in turns to tend them and muck-out. We had the run of

the adjacent farm, the barns and the apple orchards: Blenheims, Worcesters and

cider apples, with the odd crab-apple. Three of the farm's tractors, I recall,

were a bright orange Alliss Chalmer (a light weight fairly fast model which was

used mainly for towing carts along the lanes) a medium weight old Fordson and a

huge then modern bright red Case (which I believe came from Canada). I think

that the Case was a diesel and the other two were fueled by paraffin, with

petrol starting.

We had no gymnasium. On fair days, we

had exercise periods on the front lawn. Alternatively, we had school runs along

the lanes and through the fields. Our team games training was in a cow field.

We did play soccer against a few of the local schools - like Felstead Prep,

where we usually were thoroughly trounced.

The only other Ernest I ever met at

school was our goalkeeper for a time. He was highly prone to acquiring black

eyes, I recall. He had other problems though and kept running away from school,

so he did not last very long with us. We had our cycles. I was given mine by

Manfred, a school friend, who was with us for a short time before emigrating to

the States. These were mostly rather ancient models and we often scoured the

local lanes in groups or pairs. As traffic was very sparse, the roads were

relatively safe.

For recreation, we often cycled to

Hereford on a Saturday, to visit a museum, have tea, or go to the cinema to see

films like "Western Approaches" or "In Which We Serve".

Once, we went to a travelling circus in Stretton Grandison - the first I had

ever seen. On other organized occasions, we went to one of the three Malvern

towns nearby and sometimes climbed Worcestershire Beacon (just a mountain at

1000+ feet) or the adjacent hills.

The local (and the school's) doctor

needed his lawns cutting, as petrol was not to be used for this purpose. John

Eaves and I were the first to volunteer for this, with the motivation of extra

pocket money. Depending on the season, we cycled every week or fortnight to the

doctor's house in Tarrington. With John pushing and guiding and me pulling on

ropes, we managed both front and very large rear lawns in about three to four

hours, with an 18 inch roller mower. It was hard work and we soon became very

fit. After the first year, I took over the handles and another lad took my

place on the ropes. The doctor's wife very kindly provided soft drinks and

cakes or biscuits at "half time".

During the summer, there was also hop

picking. We were allowed to join the "professional" hop pickers, to

pick on weekends and late afternoons and evenings. We were paid per bushel, the

proceeds went to the school recreation fund. This was good fun. The hop-pickers

were a mix of real (Romany) gypsies and travellers from Bristol and east

London. They camped with their families in tents, or sackcloth igloo like

structures (as tinkers) and a few had old vans (somehow managing to acquire

petrol for these) in a field adjacent to the hop yards (as the fields where the

hops are grown were called). The latter looked a bit like vineyards with posts

and wire about 7-8 feet high.

Our teachers were not very keen on us

mixing too closely with the pickers' kids, as they were unlikely to have had a

bath for weeks! We found their chat, accents and street wisdom fascinating and,

of course, highly educational. I smoked my first cigarette then, an Embassy,

supplied by a tiny cheeky faced 11 year old girl urchin called Veronica, from

the hop-pickers camp. It would be unfair however to blame her for my subsequent

heavy smoking habit, which I was not to give up until my mid 50's.

There was one dreadful tragedy. Ann, on

the cross-bar of David's bike, crashed into an army lorry, which ran over her.

She died from internal injuries within minutes. She was but nine or ten years

old and such a bright, sunny and happy girl. What a tragic family: their half

brother, an airman, was reported missing about a month before this accident -

leaving Ann's other older brother Robin the only child. I am not now sure if

the father also went missing earlier. David survived, with a badly scarred leg

and with the most horrendous memory to have to live with. I remember visiting

him a couple of times at his home in Dolphin Square, Victoria in London, to try

to cheer him up during the holidays.

The infectiously enthusiastic Miss

Gardener also ran pottery classes, using the red clay we excavated from the

river banks. With her we built an outside firing kiln from fire bricks. Before

each firing, we had to collect a huge mound of wooden logs for fuel - enough to

last for 24-36 hours. We took it in shifts to tend to these day and night

continuous sessions. We set this up near the big old walnut tree - sometimes

munching these nuts when in season. I can still taste the fresh walnut flavour.

Sometimes, we toasted bread from the front of the kiln and baked potatoes and

chestnuts in the kiln on cool-down (which could take 24 hours) when firing had

finished.

Then there was the time that we

discovered the trap door to the cellar under the conservatory and a crate of

opened fortified wines, sherry's, ports and liqueurs. I cannot say that we all

acquired the taste for these - but our moderate and secret samplings from time

to time created interesting and intriguing diversions!

The school was quite enterprising also

with half-term holiday adventures. During the early years, we camped on

Tarrington Common (or more accurately, Durlow Common, I believe). These outings

usually comprised a long weekend, hauling ourselves and all the gear about a

mile up the hillside, where we camped "wild" but under supervision.

In the latter years we went into the

Black Mountains in Wales. We stayed at a tiny village called Capel-y-ffin,

between Hay-on-Wye and Llanthony. Firstly, we stayed in a Youth Hostel there,

the Blue (timber) Bungalow and then at the Monastery (which is now a hotel, I

believe). I remember the tiny sleeping cubicles, with slit church style windows

and the full size slate and mahogany billiard table, which pivoted to turn over

to form a huge dining table. We travelled there by rail, via Hereford and

Hay-on-Wye to Glasbury (the line has since disappeared). Then we walked and

climbed over the pass, with Hay Bluff (over 2200 feet) on our left and down the

Gospel Pass (which became a river in the winter). We enjoyed our adventures,

despite the mists and damp at times.

There were the usual epidemics of

children's diseases: measles and German measles, chicken pox, plus mumps, which

unfortunately I had just as I reached puberty and was extremely embarrassed,

uncomfortable and painful! I forget after which one but we had to sterilize the

entire school by fumigating with burning sulphur sticks for a whole day, which

probably put paid to all the fleas and bugs too!

On the one occasion when mother and

father visited, with her usual hawk-eye efficiency, mother discovered fleas in

the bedding. But then she could spot cobwebs at 100 paces, to the despair of

all our domestics at home! At school we also were subjected to head delousing

sessions, with special long tooth stubby fine combs and gallons of Dettol. I

think that there was an army of special district nurses ("nitty

Noras") appointed for this, in those days. Also, we had to take malt and

cod liver oil daily. I was very annoyed when aged 11, I had jaundice, knocking

me out for the best part of 10 days and completely ruining my Easter holidays

at home that year.

During the first half of 1944, London

was subjected to the V1's, the "Doodlebugs" or "Buzzbombs",

which were rocket propelled pilotless flying bombs. One fell close to my younger

brothers' school, Byron House, in Highgate Village, causing much damage and

frightening the kids, especially Peter. The school closed for repairs, so Peter

and Robin (aged 6 and 4) came to join me at Yarkhill for the three or four weeks

prior to the summer holiday break-up. Meanwhile, father arranged to rent a bungalow

in north Wales for the entire seven week vacation. Our parents, with Marian,

collected us from school. We all travelled by train, from Hereford via Shrewsbury

to Pwllheli and then by two taxis (one with all our luggage) to Abersoch. We

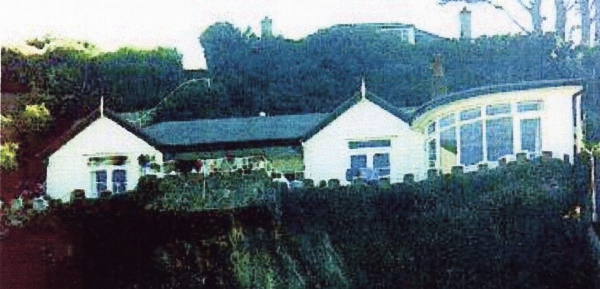

were out of harm's way for the entire summer holidays of 1944.

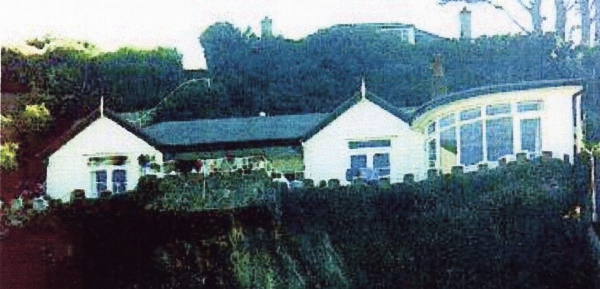

Our seaside bungalow was called

"Craig-y-ogoff" and was on the rocks, with a cave beneath it, which

was flooded at high tide. We had our own direct access down stone and concrete

steps to the sandy beach, which the bungalow overlooked. The curved extension

on the right is a more recent addition. We had a wonderful sunny August and

September there.

During my last year at St Mary's, a few

of us were billeted out, as the school house ran out of space. Six of us, all

boys, stayed at a little cottage at Shucknall, just over a mile west from the

school. This belonged to an elderly spinster who lived there and gave us a cup

of something in the morning and at bedtime. She was warm and kindly. There was

no bathroom or running water, only an outside hand pump and a "privy"

of traditional country two seat earth type at the top of her typical and

beautiful cottage garden. I shared a small bedroom with Durwood (an older boy,

who later went to and I believe eventually taught at Dartington Hall), while

the four others shared the larger front bedroom.

I remember the aroma of wax polish,

that unique gentle mellow tick of each swing of the pendulum from the

grandfather clock, the sweet smelling lavender, stock and honeysuckle and the

sharper lemon-like thyme from the garden. We cycled each way, morning and night

(sometimes running the gauntlet with local mischievous youths) - all of which

gave us a little taste of apparent privilege and independence.

Mr Paul bought a very old car during my

last term, an early to mid 1920's Singer 4 seater. The radiator cowl was

polished brass, the wheels were cast iron spoked affairs, the battery sat on

one of the running boards to the front. The brass headlamps were of the

acetylene gas type. Its top speed was about 25 mph when hot and having a crash

gearbox, its transmission ground and howled its laboured progress. The clutch

was very slow, hence gear changes were very much a hit and miss affair - Mr

Paul missed a lot but thoroughly enjoyed his new found mobility.

The war in Europe ended when I was 12,

about two months before the end of another school year. It was time to switch

to secondary education, which my parents felt would be better served by a

change of school, as there were very few qualified secondary teachers then at

St Mary's. Hence, I transferred to The Beltane School, another independent but

much larger and more progressive school, which is described elsewhere on my web

site. My time at St Mary's had been happy, despite the war creating upheaval

and making some of us boarders at a much younger age than normal.

We were all well looked after, well

treated and safe from the worst of the blitz. Although I would not have been

able to pass the Common Entrance (to Public School) examination, a few brighter

pupils managed to, so I guess that we received a reasonable elementary

education, with a sound foundation to develop into decent members of society.

Above all, most of us were happy and had been protected from war damage.

After I left, the school moved again

and became St. Mary's Town & Country School, partly as a day school back in

London, plus a boarding section, which I believe was at Stanford Park, near

Rugby in Leicestershire to at least 1949, which I believe that Miss Gardener

ran for a while. The main school remained at Eton Avenue until it was wound up

in 1982. As far as I know, there has not been any reunion event.

Copyright © Ernest Weiss 1995 -

2004 . . . www.telling-tales.fsnet.co.uk

* * *

b. Plus Reminiscences by Priscilla Wilder, née

Eaves

I never could understand the school's

name - but I understand that Heinz and Elizabeth Paul bought it with that name

sometime in the mid to late 1930's. I joined the school in 1937 and was nine

years old. It was then located in Belsize Park but I don't remember the exact

address. It consisted of two adjoining houses. The students were primarily the

children of artists (musicians, writers, film producers, actors, etc).

It was the time of the Spanish Civil

War and I remember a benefit being given to aid the anti Franco forces. Paul

Robeson's son and Stella Adler's daughter Ellen were enrolled in the school.

Stella Adler was with the Group Theater which was performing in England. Paul

Robeson was singing in England. Ellen Solevieff was one of the older children

and came from America. Her family were in the arts and her sister Miriam was a

violinist. Ellen died tragically at the beginning of World War II. In true

British fashion we were not told what had happened but several members of the

family died and I believe only Miriam survived.

The school was rather more academically

oriented than it was during the war. The Paul's were still associated with what

was their school in Berlin and the aim was to have children spend time (one

year) in each of the schools on a rotational basis. We studied English, German

and French from the earliest ages. Science education and sports were minimal,

although I do remember playing tennis once a week and going to the baths on

Finchley Road once a week for swimming.

This all came to an abrupt halt on

September 3rd, 1939 when war was declared on Germany. The next day we found

ourselves at Paddington Station with large labels hanging around our necks with

our name, the name of the school and our destination. In our case it was

Dartmouth. From there we must have been taken by bus to Beesands where the

school had found lodging in a relatively small house at the end of the beach.

My mother had come with us as one of the teachers and she was joined by my Aunt

Margie, my father's sister, who assisted in the housekeeping/cooking

department. I slept in one room in a fisherman's cottage with my mother and

Aunt. We all shared the same feather bed which I recall was wonderfully warm!

School supplies were scarce to

non-existent. We used slate from a local quarry for writing purposes and we

shared a few textbooks. There was no local library and books were borrowed.

After the first few months of the war, we couldn't swim as the beach was mined

and the fishermen had a narrow space in which to keep their boats to prevent

mine accidents. The beach was strafed by the Luftwaffe but no mines were

detonated and I recall no injuries to children or fishermen.

The greatest problems to everyone were

the oil spills from sunken vessels in the English Channel. The oil saturated

the seabirds and poisoned the fish. The fishermen would haul in their nets and

pull out large balls of tarry substance and their polluted fish and crabs.

Ultimately they caught few crabs even though Beesands was famous for large

hauls of these creatures.

When France surrendered we were

evacuated to Yarkhill in Herefordshire. The train stopped in Bristol which had

been practically flattened the night before by incendiary bombs. Fires were

burning everywhere and I remember being frightened because my grandmother lived

there. My father was on the platform and told us the family was safe. My

grandparents had bought a house just outside Bristol and spent the nights

there. I assume they took the train or bus each evening and returned to the

city in the morning. My father was in the RAF and had stopped to say hello

before leaving on assignment.

We arrived at Yarkhill and were

astonished by it's size in comparison to the digs in Devonshire. Three floors

but only one bathroom. There was, however, an outside loo. The grounds

consisted of a grass tennis court in front of the house, a large vegetable

garden to one side and an access road with farm buildings on the other.

Yarkhill Court was the home of a

gentleman farmer who was then in the armed forces. The farm grew fruit

including a variety of currents and hops. There were cows in the fields but I

am not sure whether they belonged to our farm.

Gypsies came during the fruit and hop

harvesting time to pick. We also helped with the picking and I remember loving

the smell of the hops, the warmth of the sun and the luscious berries. It was

heartwarming to see the small gypsy babies tied to their mother's back with

huge scarfs or to see them in the edge of the hop crib. It was the first time I

had seen breast feeding!

Workers were paid by the bushel

basket. The gypsies spoke some English but they conversed among themselves in

Romany. Most were illiterate and my mother would read letters from their

husbands or boyfriends who had learned to read and write in the army. I

remember admiring the bright clothes and long black hair. I thought the women

were exotic. Their life seemed so romantic. I was completely unaware of their

hard life without running water and inadequate clothing and food.

Several people involved with the school

were very special to me. Rosamund Gardener joined the staff in 1941 or 2. She

had been a teacher in Monserrat for several years and was an artist. She taught

English and Art but taught anything else that she felt was needed. She was a

fiercely independent woman, a real feminist and completely committed to

teaching. I have kept up with her over the years. She lives in Taos, New

Mexico. After the war, Roz went to the University of London and earned her Ph.D

in Psychology. While at the London school she met Dorothy Barnett who was an

archaeologist and writer. They became life long partners and Roz moved to San

Francisco where Dorothy had a house. They both lived very interesting and

productive lives. Their friends were numerous and once they retired to Taos,

Roz began painting again.

Elizabeth Paul, our Headmistress, had a

tremendous influence on me. My love of language and a certain joie de vivre,

filled me with a longing to be part of that European heritage which was so

steeped in culture, personal refinement and gentility. Elizabeth gave me my

first pair of high-heeled shoes which I wore when I took my school Certificate

Exam at the Malvern School for girls. They were taken away from me as soon as I

arrived and I never saw them again. As a teacher and friend, Elizabeth always

encouraged me and whenever I went back to England I went to see her in her

Chiltern Hills retirement house. She was a very bright and passionate woman who

played favorites but I was lucky to be one of them.

Then there was Madame Selva or was it

Silva? A diminutive but forceful woman and Elizabeth Paul's mother. She wore a

chatelaine and many keys dangled from her waist. She was the mistress of the

food and held the keys to the storeroom. She never learned more than a few

words of English which forced us to speak German to her. She communicated with

Harry (the cook and former stablehand and groom) via gesture and expressive one

word utterances of either German or English.

Harry was a marvelous character, a

rotund and jolly man who had never been married and who took the whole of the

school on as his family. I think it was the happiest time of his life. Joan

Askins told me that when the school left for Bedfordshire he tried to follow it

and walked all the way. He was either no longer needed or the school had

already moved back to London but it was a heartbreaking story.

The children I remember were Michael

Derwood, Joan Askins, the Bowleys both Robin and Ann, Ernie Weiss, Arnie

Altschul?, Andrea Strasser, the petite and beautiful granddaughter of Haile

Sellasie who was a day student. John Mates tended the garden and the Wares

(husband and wife) both taught and helped in the house for a period of time.

I took piano lessons from Michael

Mullinar and ballet lessons with his wife Mary. They lived in a neighboring

village and it was a great occasion when we saw the Mullinar's first baby,

Keith. Michael gave music appreciation lectures at Yarkhill fairly frequently

and I remember every record that he played and discussed (Das Lied von der

Erde, Harry Janos, A Child of our Time, Façade, Peter Grimes and of

course Vaughn Williams' works). The latter was Michael's great friend and

patron.

I remember plays in French and German

played in the barn behind the house. There were half-hour breaks in the morning

and afternoon when we had a slice of bread with margerine and another with jam.

We had one sweet a day which was served after supper, I believe. It was always

porridge and a slice of margerine covered bread for breakfast. The main meal

was at noon. Although most foods were limited we had plenty of vegetables,

potatoes, and fruit.

I was not a happy child, maybe none of

us were. Grown-ups did not confide in children and we were not even kept

abreast of what was going on in the war. I was always the oldest child and felt

extremely responsible. I never received any special attention and felt isolated

and lonely. There was no one to talk to and I knew that I was ignorant of many

things that other teenage girls were aware of. I worked hard and enjoyed

school. I am now grateful for our many experiences because I think we grew up

to be caring, adventurous, multilingual citizens of the world. It was indeed a

unique intellectual trip into adulthood.

Copyright © Priscilla Wilder 2003

* * *

a. 1947-48

by Gay Marks

Being so young when I first went

to Town and Country in 1947/8 means that there is no continuity to my memories

- rather a bundle of impressions - but very vivid ones at that. Mrs Paul, to

start with, was the totally unapproachable figure on the Floor Above who wore

amber beads and whose delicious-looking meals went up on a tray while we ate

disgustingly plain dinners down in the basement. In no way can I equate her

with the inspired teacher and educationalist in other accounts. Wizened Mr Paul

told us Greek myths in a thick German accent and wore a black beret.

Nobody else mentions the teachers

we had in that immediate post-war period: Mr Williams (Willy) for music:

pink-faced and jolly who conducted our "orchestra" with tremendous

gusto, or Mr Gubbins (Gubby) for maths who had greasy hair and smelt. Perhaps

they were roped in when nobody else was available and swiftly moved on.

However, I do remember Miss Bennett who was slightly fierce but nice with it.

Writing was my best subject. "Come on, now Gay, don't look like that,

we're going to read your essay out." I can still remember what it was

about: A lazy day on Hampstead heath. There was also Mrs Noyes (very nice) and

Mr Pousteau - unintentionally funny, poor bloke, and there was Miss Gardner

whom I can still see now, sporty and laughing with a lot of even teeth. She

once had to separate me and my sister who were fighting in the playground.

I fell in love with the bigger

boys one after the other from Peter H. and Peter J: to Julian C. and was

frightened like most of the girls were by fierce Eddie who had his camp round

the corner between number 38 and 40 and who terrorized us together with his

henchmen. Caroline Dimont, the actress Caroline Mortimer was in my form, and

little David Nelson who sang "Where'ere You Walk" in his angelic

voice. Carole Shelley the child actress was also there and a host of others who

probably wouldn't remember me as I was then a shy child.

Often our classes seemed to be

held with different age groups and we would have German lessons sitting under a

tree on Primrose Hill on lovely summer mornings, walking there in a crocodile

down Merton Rise, shivering in horror as we passed the grim porch of the

"Witch's House." I learnt absolutely nothing academically at St

Mary's and the fact that I scraped through the ten-plus exam must have been

partly due to the enquiring mind and intelligent outlook the school helped to

foster in us.

When I was thirteen or fourteen I

was invited back to a party there by a former pupil who had kept up with the

place, and was impressed - by what seemed to me then - the sophistication of

the kids there. So different from those of the single-sex grammar school I now

attended. Looking back I realize, not unsurprisingly so given its origins and

objectives, that Town and Country turned out a more European type of English

person. Maybe I unconsciously hankered after that, as some years later as a

young adult, I came to Italy and have lived here since. However, I still dream

of Eton Avenue.

Copyright © Gay Marks 2004

* * *

b. 1953-61

by Natalie Muzlish, née Besser

I started at St. Mary's Town &

Country School in September, 1953, when I was eight years old. The photograph

was taken during my first year in the Spring of 1954. It is of Class Lower IV,

with me at the front.

After

almost half a century, I can recall only a few names. Immediately behind me

but to my left is Geoffrey Burns. The boy in the row behind Geoffrey is Keith,

behind whom is Peter (who now runs G-Plan Furniture). Beside Peter is Stella

Riser and then another Keith.

After

almost half a century, I can recall only a few names. Immediately behind me

but to my left is Geoffrey Burns. The boy in the row behind Geoffrey is Keith,

behind whom is Peter (who now runs G-Plan Furniture). Beside Peter is Stella

Riser and then another Keith.

The only other school pupil names that

I remember are: Anne Cruikshank, Gillian Glass, Glenys Jones and Angela

Pleasance (who became an actress). Also, Larry Adler's and Andre Previn's

children were at St. Mary's - but I do not recall their names.

I remember that the school

at 38-40 Eton Avenue seemed to be very large, with two houses built together

and with very high ceilinged rooms. I was a very shy person, not knowing the

art of joining in and being rather nervous of being intertwined in a seemingly

large co-ed school. In looking back, although it seemed large at the time, in

fact the school was very small.

The playground had a tarmac surface, on

which we had to queue up before being allowed into the back entrance once the

school bell went. The playground was split into two parts; one for the younger

children and the main entrance for the older ones. On entering the building

from the back, you came across pegs for the children to hang their coats and

satchels on. There was another room for the older children to hang their own

things on. The kitchen and dining room were also to the rear.

The house consisted of three floors.

The ground floor had two large rooms, which were used for assembly, These could

be divided to make individual rooms. The back part was used as a stage, when

plays were being preformed. This happened on a regular basis. It has some wood

placed on it to make the floor higher that that in the other room. The plays

performed included Tiki et Taki and The Wind in the Willows. The latter seemed

to be a great favourite, as I remember that it was performed quite often. In

fact I played Mollie in one version. I do not recall what year that was - but I

know that I had a mask and a tail and remember looking very stupid. The other

room was also used as a classroom in later years.

Mrs. Paul's room was on the next floor,

where we were sent if we were naughty. I remember having to wait outside until

she was free to have our punishment dealt out. The rest of the house consisted

of more classrooms, with the art room on the top floor. All the teachers were

specialists in their subjects. The art teacher was an artist, the French

teachers were fluent in French, and so on.

When a new teacher, Mr Brown, arrived,

we decided to have a bit of fun with him. He had not known the area, so, on one

of the local outings he arranged, we took him out and around, getting him

completely lost. My memories of him are very vague - but it has always stood

out how difficult a time he had and, looking back, I felt rather sorry for

him.

Our essay teacher, Miss Jean Bennett taught at the school for just one day a week. She lived in Reigate, in Surrey,

and brought her small terrier dog with her. She always expected us to hand in a

weekly essay. For this I won a prize of a bird book, which I still have after

41 years. At the time I could not see the benefit of her lessons and thought it

just a chore to have to write these essays. Yet, today I can honestly say that

it had stood me well in life for writing letters and so on.

One subject Ms. Bennett asked us to

write about, I recall, was Churchill. I had not heard of this man at the time

and interpreted this to be Church Hill and wrote an essay about that. In fact

she read out my essay at Assembly, where she would read out the most unusual

essays of the week. I do not know, looking back, whether I was proud, or just

purely embarrassed, as obviously I had got the wrong concept of what she was

trying to achieve. Ms. Bennett gave us the choice of any one of three essay

subjects each week. I am sure that she did not think that anyone could have

misinterpreted her ideas so badly - but perhaps it is good to have different

inputs about every topic.

Holidays were the highlight of the

school year. They seemed to be for nearly three months in the summer. I am sure

overall that they were no longer than elsewhere - but they were always taken as

a block. Opposite St. Mary's was another school where the pupils wore green

uniforms. They were known as the "Green Flies."

Mrs Paul always believed in psychology

and was quick to involve parents. I thought that I was different - but knowing

better now, I feel that too much emphasis was placed on this. A child will

develop and grow with love and should not be made to feel different. I feel

that in today's society Mrs. Paul got it wrong - but who can say what was right

or wrong 40 odd years ago?

Mrs. Paul was a linguist and spoke

fluent French and German. She was a forbidding type of person, who seemed to

tower over everyone. She always believed in getting the parents involved with

pupils' punishments and disciplining at every opportunity - to the detriment of

the child in some circumstances. After over 40 years since leaving the school

in 1961, I now can look back and see the bigger picture. Mr Paul wore a cap and

could be seen around the school pottering about here and there. I never had

anything to do with him.

We were taken to Haverstock Hill when

we were till fairly young and I remember digging up some old stone statue like

parts. I never heard what actually happened to them. All that I can remember is

coming back full of dirt and that we all must have enjoyed the event.

The choir sang on the radio when I was

quite young. We were taken to central London and sang our hearts out. This was

quite something, as not many schools had the privilege.

Our history and singing teacher was

Mr. Myerscough (pronounced "Miasco"). He later changed his name to Mr

Neville, explaining that too many people found difficulties in pronouncing his

original name properly. He smoked non-stop, lighting one cigarette after

another. He was certainly quite a character and even composed a school anthem:

Esta Maria Scholar (excuse the spelling, I never took up Latin, preferring to

study German instead). The words I recall were something like: "Esta Nobis

in canticha pro examina." It certainly would be interesting to hear if

anyone else remembers this.

Mr. Myerscough was a larger than life

personality, with enormous enthusiasm, which he down loaded into our young

minds. His love of his subject was very apparent. I can hardly recall anyone

else that I have ever met who made such an impact on me and which has lasted

for so many years. He was very unique and most dedicated to the cause.

A husband and wife team, Mr. and Mrs.

Sylvane, taught English and Maths. They were both rather small, thin and stern.

Mrs Sylvane had a pointed nose and wore glasses. They both got good results

though.

There was a privet bush outside the

school and one day I found a stick insect on it. The school kept such

specimens, from which we learned some basic biology. We had to supply them with

privet leaves.

Cookery classes were held in the dining

room. We had to bring in the ingredients to make the food. This was more fun

than anything else, as the food had to be transferred to the kitchen to cook in

the ovens there. Each table had about six children trying to achieve some

resemblance of what we were supposed to be making. Naturally, we had to tidy up

the mess. Once cooked, we were presented with the results to take home to our

parents. We had to jot down the recipe and how we achieved it in our exercise

books. I do not remember any very successful outcomes.

The cooks prepared lunches on the

premises. We had to queue up for lunch in classes, the meals being dished out

by the cooks. I remember that it was always called : "meat, potatoes and

greens." There was also some kind of pudding. These meals were served with

a multiple of sittings, so we had to eat up fairly fast and then go out and

play. The tables were in lines across the room and a person was elected to tidy

up afterwards.

Swimming was at the local baths in

Finchley Road. As I did not swim, I watched from upstairs, which I found rather

boring. All the swimmers had to change as fast as possible, as the whole

session, including transport, etc. was for such a short time. All P.E. and

games was undertaken at Haverstock Hill. In the summer we played tennis and in

winter it was hockey and netball.

When studying for the "O"

levels we went to see Merchant of Venice and other Shakespeare plays. The

school believed in the cultural things in life, which was definitely evident

with the many different things the school undertook. For the French

"O" level we studied "Les Enfant Terrible," which I found

very hard and have never enjoyed it until today.

I have since come to appreciate some of

Shakespeare's works, once I went to see the plays when I was older and could

understand better the finer points. It was not like studying every passage and

trying to grasp what the writer was meaning and by having to comment on each

sentence.

After-school activities consisted of

ballet classes, which I was never fortunate enough to take part in. Naturally,

at the end of each school day, things were rather hectic. Parents arrived to

pick-up children, rushing for the buses to go home to start and complete the

homework, which was to be handed in the next day.

On Guy Fawkes night (5th. November) the

school had a fireworks party, to which we were invited to return and have some

fun. This went on for about five years until it was no longer feasible

(probably for safety and insurance reasons).

The most advantageous aspect of St.

Mary's over most other schools was that the class sizes were small. It seemed

to me that there were no more than 20 pupils to a class. We received much more

one-to-one learning, especially where individual problems arose. There were

still dententions - but these would only last for about half an hour, so you

could travel home by catching the next bus.

The school uniform was tartan skirt and

a turquoise blazer. The boys wore grey. The school also had some boarders - but

I do not know where they stayed, as this did not concern me. All that I can

remember is that the boarders were given some refreshment after the day's

school session had finished.

If anyone else remembers anything more,

or can put some light on the years after 1961, we would love you to bring the

school memories up to date. I know from friends who lived in the Swiss Cottage

area that they had information on it, right up to 1982.

Copyright © Natalie Muzlish 2002

. . . . .

* * *

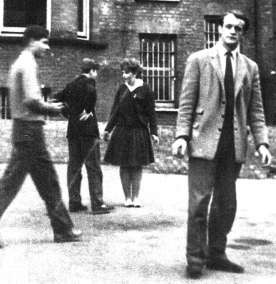

Photo Montage

The following dozen photographic images

are from the early 1960's. These are shown here thanks to former pupil Lizabeth

Flint, via Natalie Muzlish - all due to our common membership in Friends Reunited.

Unfortunately, only a few of the names are remembered. Should anyone be able

to identify any of those not named, please email direct. One such respondent was

George (Juerg) Haller (Photo 9) - from Switzerland - with a few more names,

plus the addition of the last four photos from his 6x6cm Ilford Sporti camera

- (thanks George!).

Names are listed from left to

right

Photo 1. Lillian Trigg, Pam Thompson, ?,

Juliet Glaister, ?

Photo 2. ?, Angela

Photo 3. Michael Spencer, ?, Timothy Grimes,

?, ?, ?, Jackie, ?, Susan Elman

Photo 4. Mr & Mrs Sylvain

Photo 5. Mr Nash (Pianist), Mr Myerscough

[Mr. Neville] (History), Miss Bunting

Photo 6. ?, ?, Angela, Mr David Cheetham

(English)

Photo 7. ?, Juliet, ?, ?, Miss Bunting, ?,

Sharon Gold, ?, ?

Photo 8. Donald Atkins is to the right

of Michael Schmidt

?, ?

Photo 9. George (Juerg) Haller, Joanne

Gandasoebrata, John Walton

Photo 10. Ben Trisk*, Joanna McEvoy

(*A south African, who excelled at

Tennis - info. thanks to Giles Thomas, who attended 1962-64.)

Photo 11. ? - ?

Photo 12. ? - ?

Photo 13. 1960 - on return from Southend

outing: Michael Schmidt, Gerald Davies , John Walton, Peter ?

Photo 14. Same day as 13. above: Gerald

Davies , Leslie Taussig(?), George Haller (behind), Robert ?, John Walton (behjind),

Peter ?

Photo 15. Same day as photo 13: George

Haller at Swiss Cottage bus stop on Finchley Road

Photo 16. In school playground: Timothy

Grimes(?), George Haller, Sarah Walton (John's sister), Peter Haller (George's

brother)

* * *

Copyright © Telling-Tales 1995 -

2004 . . . . . www.telling-tales.fsnet.co.uk (offline)

Beesands is a tiny village on the Start Bay

shore between Torcross and Start Point in the southern most part of Devonshire

known as the South Hams. This beautiful fertile region of English countryside

lies between the English Channel and perhaps the most rugged barren "last

wilderness" in the southern half of Britain: Dartmoor.

Beesands is a tiny village on the Start Bay

shore between Torcross and Start Point in the southern most part of Devonshire

known as the South Hams. This beautiful fertile region of English countryside

lies between the English Channel and perhaps the most rugged barren "last

wilderness" in the southern half of Britain: Dartmoor.  Yarkhill in Herefordshire is

in the heart of rural Britain, in the rain shadow of the Welsh Black Mountains

betwixt the city of Hereford and the Malvern Hills. We moved into Yarkhill Court,

a small manor house attached to a working mixed farm, about six miles east of

Hereford and lying between the villages of Tarrington and Stretton Grandison.

Our local Great Western Railway station was Stoke Edith (now no longer existing,

I believe) less than half a mile from Tarrington and about 1.5 miles from the

school.

Yarkhill in Herefordshire is

in the heart of rural Britain, in the rain shadow of the Welsh Black Mountains

betwixt the city of Hereford and the Malvern Hills. We moved into Yarkhill Court,

a small manor house attached to a working mixed farm, about six miles east of

Hereford and lying between the villages of Tarrington and Stretton Grandison.

Our local Great Western Railway station was Stoke Edith (now no longer existing,

I believe) less than half a mile from Tarrington and about 1.5 miles from the

school.

After

almost half a century, I can recall only a few names. Immediately behind me

but to my left is Geoffrey Burns. The boy in the row behind Geoffrey is Keith,

behind whom is Peter (who now runs G-Plan Furniture). Beside Peter is Stella

Riser and then another Keith.

After

almost half a century, I can recall only a few names. Immediately behind me

but to my left is Geoffrey Burns. The boy in the row behind Geoffrey is Keith,

behind whom is Peter (who now runs G-Plan Furniture). Beside Peter is Stella

Riser and then another Keith.